Daniel Kigeya’s graduation from West High School in 1997 was one of the loneliest days of his life.

“I remember walking across the stage and then leaving there and going home and not celebrating,” says Kigeya, (pronounced Key-gay-ya) who returns to West this fall as its new principal.

He did not feel like he belonged at the school, where less than 10% of students were Black like him, and where many of his Black friends had dropped out before their senior year, including some who had been Kigeya’s best friends since he’d arrived in Madison as a 10-year-old African immigrant.

While Kigeya lived with college-educated parents in a middle-class home rich with books, newspapers and magazines, many of his friends came from households where money and food was tight, where they had to care for siblings, and where the family had little experience with academic success to motivate them and help them persevere when they fell behind in school.

His experience and seeing other students struggle will make him a better principal. Kigeya is on a mission to lead and lift up the school community in continuing what he calls West’s “world-class” education while tackling the inequities, isolation and pressures he remembers. He wants West to be a place where all students feel they belong and are supported in becoming the people they want to be.

Education as a family value

On a rainy day in mid-May, Kigeya sits for an interview in his office at Sennett Middle School on Madison’s East Side, where he has been principal for the past five years. A difficult year is winding down. Although school has been in-person all year the Covid pandemic has caused extensive and ongoing suffering and learning setbacks in a community where two-thirds of students live in low-income households.

Many parents and guardians of Sennett students are essential workers who could not work remotely and got COVID, lost loved ones to the disease, and struggled to maintain housing, food and other basics while supporting their students in remote learning.

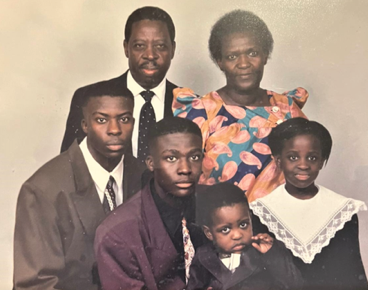

The weight of these losses and the approaching one-year anniversary of his father’s death on May 23, 2021, have Kigeya reflecting more deeply on his personal journey to the West High principal’s role than he might otherwise.

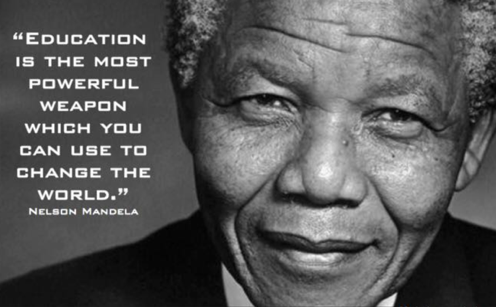

Glasses and a mask make it hard to see his facial expressions, but the stories spool out after he is asked why his Facebook page bears a closeup photo of Nelson Mandela and one of Mandela’s famous quotes: “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

Mandela, hero of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, spent 26 years in jail before becoming that nation’s first democratically elected president.

“Nelson Mandela is, from a distance, somebody I revere because he’s African – I’m African — and my background was heavily influenced by education,” Kigeya says.

“The image encapsulates the core principles my parents instilled in me growing up. One, remember your faith. Two, always uplift and remember your family. And three, service. And for them, it was service through education.”

Kigeya’s father, Joshua Kigeya, had to work in the fields in Uganda as a young child to pay for his primary schooling. A government scholarship sent his father to college in India until Idi Amin, who came to power in Uganda in 1971 through a military coup, asked Joshua to become his personal secretary.

Back in Uganda, Joshua Kigeya was advised by his father not to work for Amin because government workers were disappearing under his watch. While initially popular, Amin became known as the “Butcher of Uganda” for his brutality to his own people that resulted in more than 300,000 killed and many others tortured.

Joshua Kigeya, his pregnant wife Abby and their first son fled in the middle of the night to Kenya, where Daniel was born. In 1979, the family returned to Uganda when Amin was deposed, but the country’s economy, health care and education were in shambles and the family soon moved to the United States, with an eye on better educational opportunities.

They settled in Michigan for a few years but eventually ended up in Madison, where Joshua Kigeya helped his good friend start Living Bread Bakery and also began working toward his doctorate degree at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He earned that Ph.D., and became a UW-Extension agricultural professor.

At times, when Joshua Kigeya had a light load and there was a need, he would substitute teach physics at West High School or go to Oakhill Correctional Institution outside Oregon to help teach prisoners how to read.

“He would always say, ‘You always need to remember those that are less fortunate’,” Daniel Kiegya recalls. “That really informed my trajectory and is kind of how I’ve navigated working in education.”

His mother, a minister’s daughter from a more affluent Ugandan family, was a schoolteacher in Uganda. Once in the United States, she was not certified to teach, so she began working as a certified nursing assistant. She continued advancing her schooling and become a licensed practical nurse and then a registered nurse.

Caring for people was the way Abby Kigeya served, but education remained a touchstone. Daniel recalls his mother would often remind her four children: “Education is something that no one can take away. So get it.”

“Total War in My Head”

His parents’ words and deeds – and their expectations he would go to college — were powerful academic motivators for Kigeya. But he was also feeling peer pressure, the pull of wanting to hang around with friends who started to skip classes.

“I recall looking out the window and seeing my friends leave, like, early in the afternoon and having this total war in my head of, ‘Man, I want to go out with them,’ but then also knowing I’ve got a quiz on Thursday,” Kigeya says. “’And if I get this unexcused absence, I’m not going to be able to take that quiz or whatever it was.’ I would really have that tussle in my head about how I organized my high school experience.”

He became an expert in the calculus of doing just enough to stay eligible for playing on the high school basketball team and to protect his GPA in his core classes so he could get into college. “I remember loving basketball practice so much that there was a day that I was legitimately sick at home and I still crawled out of bed to go to school.”

Kigeya also credits teachers Gene Delcourt, Chris Vasquez and Senora Llera with throwing him a lifeline when other friends were bailing out of school.

During class debates on contemporary issues, Delcourt often reaffirmed Kigeya’s thoughts with, “That’s brilliant, man.” Vasquez would not let him slide in Spanish class and made eye contact in the hallway every time Kigeya walked by. Senora Llera would work with him after class the last period in the day to help him understand and complete assignments he was struggling with.

“She would not let me fail. And then it got to the point where it turned into I didn’t want to let her down,” he says.

Kigeya was accepted to UW-Madison and learned fairly quickly that West had provided him with the academic foundation he needed to succeed at the university.

He was closing in on his undergraduate degree in legal studies and planned to enroll in law school when he realized he wasn’t passionate about researching the law. What he did love was his job working with teenagers at the community center in Eagle Heights, the neighborhood where his family had moved when Kigeya was in middle school.

Housing UW-Madison students and staff with families, Eagle Heights had many international families like his own. Kigeya started a teen night and tutoring programs that helped residents navigate the challenges of being teenagers in America while trying to meet their immigrant parents’ cultural and academic expectations. He organized international nights, bringing families together to celebrate and build community, and ran basketball and soccer tournaments.

When the community center’s manager suggested he go into social work instead of practicing law, Kigeya wrestled with the decision. Becoming a social worker was not the dream he had long nurtured, nor would it be an easy way to support a growing family. He and his then-wife, April Kigeya, had a son, Demitrius. A daughter, Kenya, was on the way, followed later by daughter Jazmin and son Tyson.

But Kigeya took the leap of faith. He entered UW-Madison’s School of Social Work and also ran UW’s PEOPLE program at West High School. The People program recruits low-income and potential first-generation college students to help prepare them for college and provide them a four-year tuition scholarship to UW.

After earning his master’s degree in social work, he completed a graduate degree from UW in Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis (ELPA). He joined Oregon Middle School as a practicum student and after graduating, worked as the School of Hope Coordinator there. Principal Jim Pliner, his practicum advisor, mentored Kigeya and gave him a window into being a school administrator.

The two often discussed how to disrupt the inequalities in Dane County to improve educational outcomes for students of color. Among those inequities: more than 74% of African-American children in Dane County lived in poverty in 2011, while only 5.5% of white children did, and big gaps existed in reading proficiency, graduation rates, school suspensions and on and on, according to Race for Equity: A Baseline Report on the State Of Racial Disparities in Dane County.

“My whole plan was to be an elementary school principal in Madison, get them early, make sure we build that strong foundation of early literacy, teach them how to read, think critically at that age. That opens up way more opportunities as they get older,” Kigeya says.

But opportunity knocked for him to work with older students. He became a social worker with Sun Prairie schools, then an associate principal at Verona High School before accepting the Sennett job in 2017.

“I’ve loved every second of it,” Kigeya says. “Middle school students’ brains are scattered, they’re all over the place. But they love coming here and they’re still malleable. They want to be directed. They want to be loved, cared for, which is what we’ve been able to establish here — a culture of truly caring deeply for our students.”

Sennett is a working-class community with predominantly students of color: 36% are Latinx, with most learning English as a second language; 30% are African American or biracial, most of whom identify as African American; and 30% are white. Sixty-eight percent of Sennett students qualify for free and reduced lunch.

Despite all the efforts families made during the pandemic, students’ health and academic achievement suffered. Kigeya and Sennett staff have been emphasizing the social and emotional needs of students first.

“One of the first questions we ask when they come in late is, ‘Have you eaten? Did you get breakfast? How are you? How are you doing?’” he says. “Let’s make sure that when we see someone that might be down and hurting, we’re providing them with that support they need. When we can create that for them, we can now focus on the academic side of things.”

One sign this approach is working is the large number of Sennett students accepted into UW’s PEOPLE program. “Despite (the challenges), most of our scholars continue to show up every day with a smile on their face, thinking positively about their future trajectory and what they want to do,” Kigeya says.

Making a difference for West students

He is excited about returning to West High School as its principal this fall. He wants to ensure West continues offering its “world-class education.” He also wants to open up more avenues to success — more access to core curriculums and athletics so all students can find something they’re interested in, find that reason to be in school every single day. He vows to be a champion of racial and social justice.

“I’m going to ensure that those students that walk into the building know they are cared for and they’re valued,” he says. “That will involve acknowledging them as they show up. They’re taking care of siblings but also focusing on, ‘How do I get my education?’

“We tap into that. We say, ‘You have the ability to be responsible because here’s the evidence of it. You have the ability to overcome this challenge in your life. And I see you do that every day.’ We have to be able to provide that for every student.

“I am going to make sure that I’m tending to the needs of my staff and their personal families so that I can call on them to tend to our Madison West family and the students that enter the building.”

Just as teachers Gene Delcourt, Chris Vasquez and Senora Llera did for him a quarter-century ago. “That experience allowed me to develop this mindset that just because it’s hard doesn’t mean I can’t learn it. Just because it’s hard doesn’t mean I shouldn’t do it,” he says. “You will survive and you’ll be better for it. And because they were able to provide that for me, I’m here.”

Reposted from Madison Public Schools Friends & Alumni Network website. Copyright 2022.